Clinging Onto Hope: Navigating polarising narratives within the Israel-Palestinian conflict

Marina Cantacuzino, Founder of The Forgiveness Project, writes on countering divisive attitudes in light of news coming out of the occupation.

As the world woke up to the horrors of Hamas’s brutal assault on Israel on October 7th, deep divisions were cemented and sown. I watched as the tit-for-tat rhetoric of ‘if you’re not with us you’re against us’ took over our airwaves and timelines; and then as these same divisions played out in families, communities, in classrooms and workplaces.

Nuance, complexity, and the holding of two perspectives concurrently were lost in this polarisation of opinion. And because cruelty and excessive butchery can destroy the possibility of compassion, for many it soon became almost impossible to empathize with both sides at the same time. Dialogue was an instant casualty of this binary narrative, while Rumi’s field ‘beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing’ became unreachable terrain.

Like others working for peace and reconciliation I felt heartbroken and powerless. At first, I didn’t know how to respond as my social media timelines hardened into black and white thinking. I felt my heart constantly wrenched in both directions. Even some of those who had been peace advocates took positions with one Anglican vicar stating categorically that this was not the time to think of both sides.

Julie Siddiqi, the founder of Together We Thrive, a platform for Muslim women was like me confused about speaking into this space. She told me she was receiving a lot of criticism for not using the words Ceasefire, Genocide or Holocaust. “I have had close friends turn on me in ways I was not expecting nor properly prepared for,” she said. In this gulf of pain the Palestinian story became one of numbers rather than people, while many Israelis felt their trauma was being met with a deafening silence. When I reached out to the Israeli film-maker, Yulie Cohen, to say I was thinking of her she replied: “Your email is very meaningful for me; many people whom I know and know me well through the years and my films didn't write a word and it says it all.”

A young friend who has been a part of the Jewish Bloc on the pro Palestinian marches was upset with me for not joining her. She said I had marched with passion and fury against the war in Iraq in 2003 (an event which led to me founding The Forgiveness Project) so why did I not feel the same degree of fury now? I found it hard to explain why these marches with their banners and flags didn’t feel an effective space for me to protest even though I knew they grew out of a desperate need to save lives; even though I too wanted an immediate cease-fire and believed the marches were an expression of solidarity and helplessness rather than filled with hate.

And so when The Forgiveness Project was invited to join the Together for Humanity vigil – a coalition of political, faith and community leaders aiming to combat extremism and bring people together - for many of us who had been looking for another way it felt like finally we had found space to breathe. Politicians from all three main parties spoke alongside faith leaders from Islam, Judaism and Christianity, plus a Palestinian and an Israeli whose lives had been torn apart by the present conflict. As founder of The Forgiveness Project and also representing our storyteller, Jo Berry’s organisation Building Bridges for Peace I was invited on to the stage to light a lantern for peace. There were no flags, no banners and no slogans.

Later that evening I facilitated a discussion between two members of the joint Israeli/Palestinian peace organisation The Parents Circle. Robi Damelin had come to London from Israel and Mohamed Abu Jafar spoke on a screen in the West Bank. Here was an Israeli mother who had lost her son to this intractable conflict and a Palestinian man whose 14-year-old brother had been shot by an Israeli soldier manning a tank – both were uniquely qualified to talk about grief and conflict in the context of holding onto our shared humanity.

“I beg you not to take sides,” Robi said, “because your opinions are importing our conflict into your country and creating hate between Jews and Muslims. It doesn’t help us.” She wasn’t saying don’t protest, she was just saying do it with less righteous anger, and demand an end to violence and the occupation with an emphasis on peace and inclusion. For me the “both sides” argument doesn’t mean turning a blind eye to the inequality between these two sides. It doesn’t mean being neutral. It means recognising that there is pain and trauma in both communities and navigating around this agony. If you don’t acknowledge this, you create a vacuum of silence. From talking to an Aboriginal elder in Australia I know that silence leads to erasure, and erasure is just another a form of oppression. In silence wounds deepen which is why victims always long for acknowledgement of their suffering. Nelson Mandela knew that silence needed to be filled with compassion, declaring during a visit to the Aboriginal people that, “Leaving wounds unattended leads to them festering, and eventually causes greater injury to the body of society.”

Nelson Mandela also believed in the power of forgiveness. But in the heat of conflict when people are hell-bent on winning or surviving, when families are traumatised and unsettled, there is no place for forgiveness. Only much later in the aftermath of conflict, when there’s a desperate need to find a new way forward, might a forgiving heart begin to heal old wounds.

Right now, such is the level of mistrust and rage, it is hard to imagine forgiveness ever being used as a tool for repair. But from the many restorative narratives that The Forgiveness Project has collected and shared, there is one critical ingredient to forgiveness that might be of use – curiosity. Certainly, being curious about your enemy is difficult when people feel threatened, but in London Robi Damelin urged the audience to stop holding such certainty in their opinions and instead to reach out and explore the story of perhaps a single Palestinian under siege in Gaza or one Israeli hostage. She was talking about rehumanising the other by looking with new eyes and a sense of curiosity.

We have to think beyond binaries, because the alternative is a cauldron of blame and competing narratives. Last night a friend wrote to me saying, “Somewhere in the middle we will meet with a new consciousness that embraces complexity rather than being exploited by the sides we take”. Her words reminded me of Albert Einstein who famously said: “No problem can be solved from the same level of consciousness that created it.”

Perhaps this new consciousness will mean being able to embrace complexity and contradiction at the same time as holding a deep reverence for the sanctity of every human life., Perhaps even this small force of energy is currently being seeded and harnessed by grass-roots organisations round the world like the Parents Circle or the Together for Humanity coalition.

Marina is also a journalist, author, broadcaster and host of The Forgiveness Project’s The F Word Podcast. Her books include The Forgiveness Project: Stories for a vengeful age, Forgiveness is Really Strange, and Forgiveness: An Exploration.

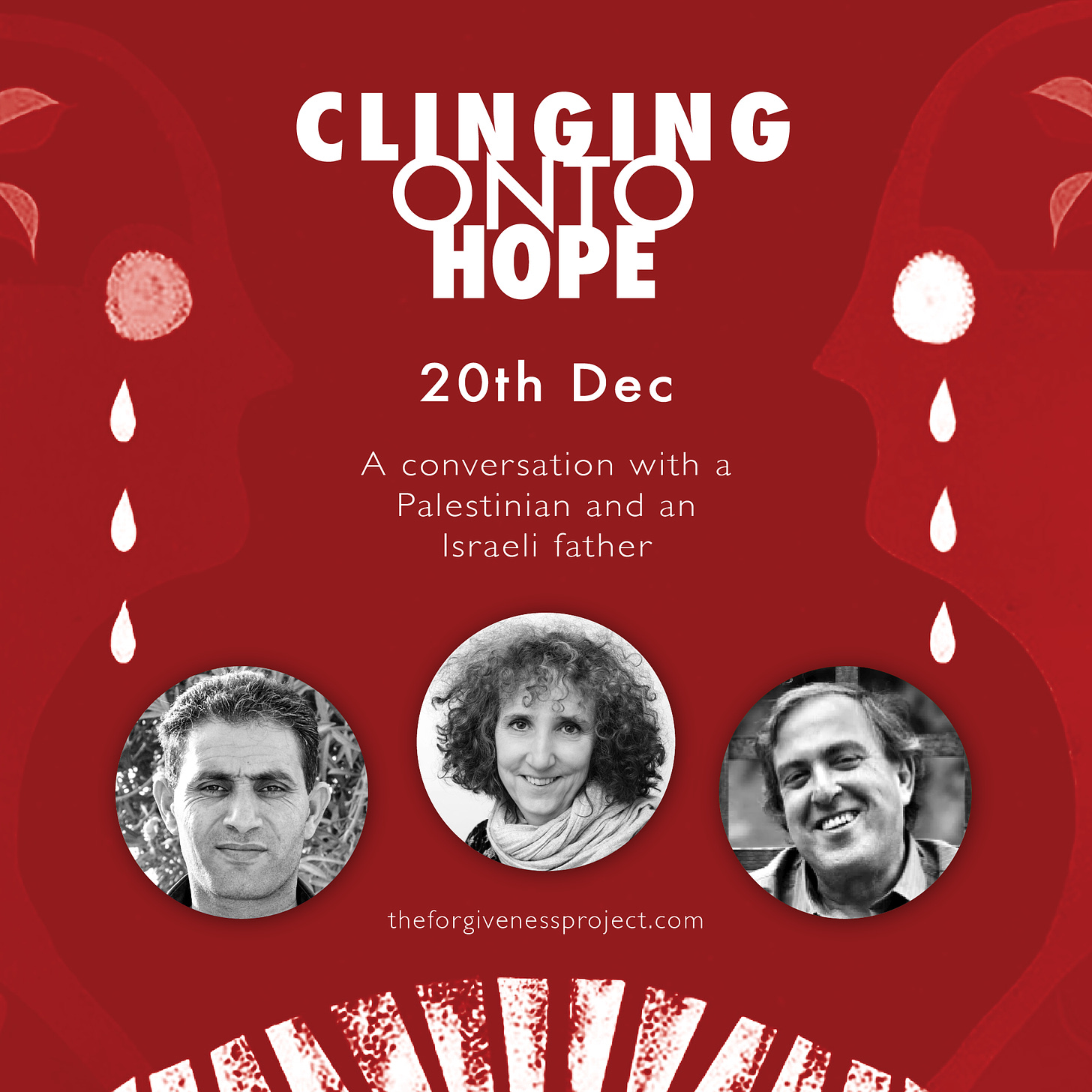

VIRTUAL EVENT: ‘Clinging Onto Hope’

On Wednesday 20th December at 5pm GMT, Marina will be in conversation with Bassam Aramin, a Palestinian and Rami Elhanan, an Israeli, whose lives were brought together by grief. In 1997 Elhanan’s 13‑year-old daughter Smadar was killed by a suicide bomber. In 2007 Aramin’s 10-year-old daughter Abir was shot by an Israeli soldier. These two fathers who met who through the Parents Circle Family Forum (a joint Israeli-Palestinian organization of 700 bereaved family members) are uniquely qualified to talk about these issues.

Hi friends. Looking forward to the presentation. I have signed up but no tickets yet in my inbox. Should I just be patient?